Next Launch

Total Students

2,609

Total Launches

683

Eggs Survived

418 61.2%

Rockets Survived

536 78.5%

Aug. 1, 2016

Is there a super-Earth in the Solar System out beyond Neptune?

by Ethan Siegel

When the advent of large telescopes brought us the discoveries of Uranus and then Neptune, they also brought the great hope of a Solar System even richer in terms of large, massive worlds. While the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt were each found to possess a large number of substantial icy-and-rocky worlds, none of them approached even Earth in size or mass, much less the true giant worlds. Meanwhile, all-sky infrared surveys, sensitive to red dwarfs, brown dwarfs and Jupiter-mass gas giants, were unable to detect anything new that was closer than Proxima Centauri. At the same time, Kepler taught us that super-Earths, planets between Earth and Neptune in size, were the galaxy's most common, despite our Solar System having none.

The discovery of Sedna in 2003 turned out to be even more groundbreaking than astronomers realized. Although many Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) were discovered beginning in the 1990s, Sedna had properties all the others didn't. With an extremely eccentric orbit and an aphelion taking it farther from the Sun than any other world known at the time, it represented our first glimpse of the hypothetical Oort cloud: a spherical distribution of bodies ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands of A.U. from the Sun. Since the discovery of Sedna, five other long-period, very eccentric TNOs were found prior to 2016 as well. While you'd expect their orbital parameters to be randomly distributed if they occurred by chance, their orbital orientations with respect to the Sun are clustered extremely narrowly: with less than a 1-in-10,000 chance of such an effect appearing randomly.

Whenever we see a new phenomenon with a surprisingly non-random appearance, our scientific intuition calls out for a physical explanation. Astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown provided a compelling possibility earlier this year: perhaps a massive perturbing body very distant from the Sun provided the gravitational "kick" to hurl these objects towards the Sun. A single addition to the Solar System would explain the orbits of all of these long-period TNOs, a planet about 10 times the mass of Earth approximately 200 A.U. from the Sun, referred to as Planet Nine. More Sedna-like TNOs with similarly aligned orbits are predicted, and since January of 2016, another was found, with its orbit aligning perfectly with these predictions.

Ten meter class telescopes like Keck and Subaru, plus NASA's NEOWISE mission, are currently searching for this hypothetical, massive world. If it exists, it invites the question of its origin: did it form along with our Solar System, or was it captured from another star's vicinity much more recently? Regardless, if Batygin and Brown are right and this object is real, our Solar System may contain a super-Earth after all.

This article is provided by NASA Space Place. With articles, activities, crafts, games, and lesson plans, NASA Space Place encourages everyone to get excited about science and technology. Visit spaceplace.nasa.gov to explore space and Earth science!

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

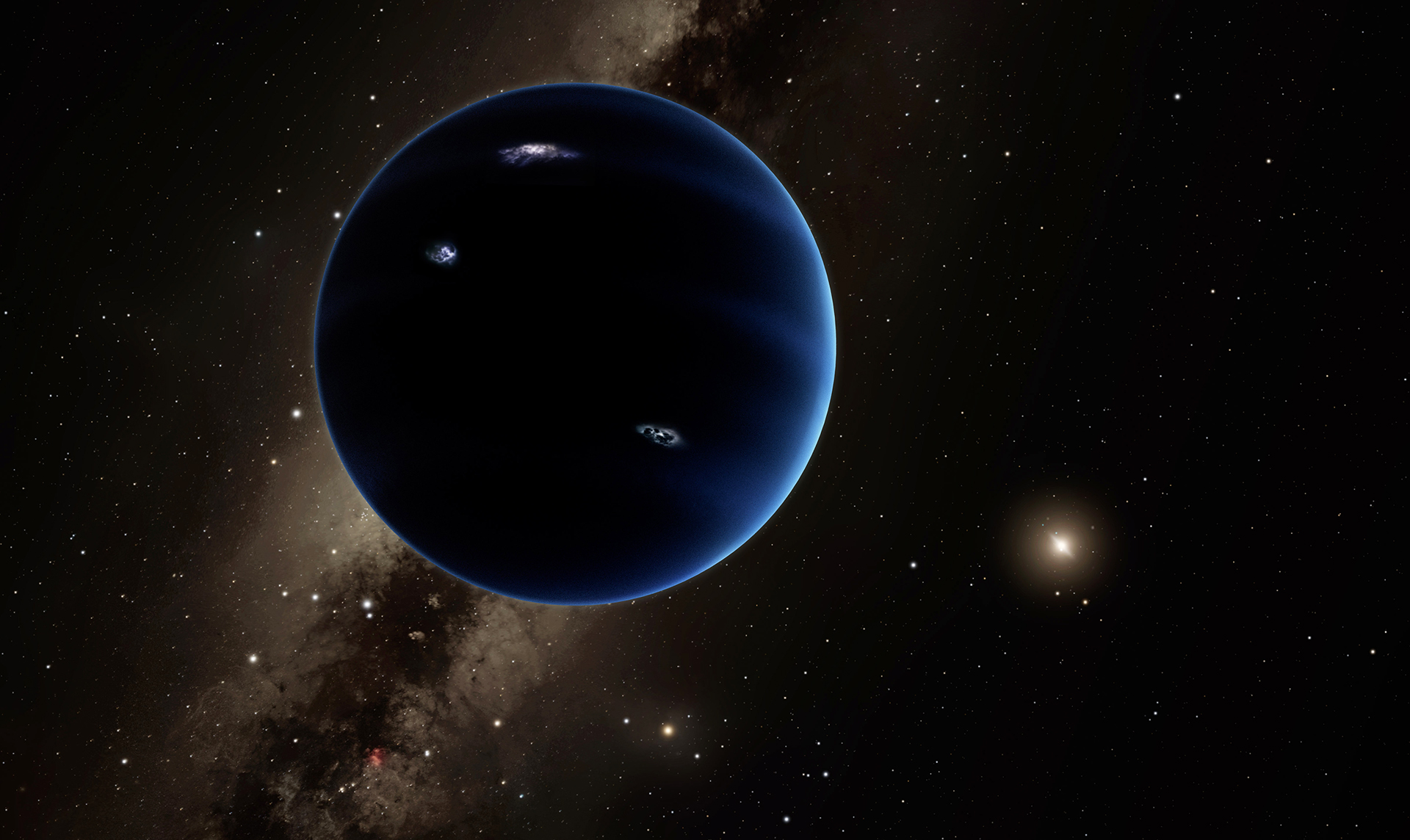

A possible super-Earth/mini-Neptune world hundreds of times more distant than Earth is from the Sun. Image credit: R. Hurt / Caltech (IPAC)

A possible super-Earth/mini-Neptune world hundreds of times more distant than Earth is from the Sun. Image credit: R. Hurt / Caltech (IPAC)

Sept. 1, 2016

One Incredible Galaxy Cluster Yields Two Types of Gravitational Lenses

by Ethan Siegel

There is this great idea that if you look hard enough and long enough at any region of space, your line of sight will eventually run into a luminous object: a star, a galaxy or a cluster of galaxies. In reality, the universe is finite in age, so this isn't quite the case. There are objects that emit light from the past 13.7 billion years--99 percent of the age of the universe--but none before that. Even in theory, there are no stars or galaxies to see beyond that time, as light is limited by the amount of time it has to travel. But with the advent of large, powerful space telescopes that can collect data for the equivalent of millions of seconds of observing time, in both visible light and infrared wavelengths, we can see nearly to the edge of all that's accessible to us.

The most massive compact, bound structures in the universe are galaxy clusters that are hundreds or even thousands of times the mass of the Milky Way. One of them, Abell S1063, was the target of a recent set of Hubble Space Telescope observations as part of the Frontier Fields program. While the Advanced Camera for Surveys instrument imaged the cluster, another instrument, the Wide Field Camera 3, used an optical trick to image a parallel field, offset by just a few arc minutes. Then the technique was reversed, giving us an unprecedentedly deep view of two closely aligned fields simultaneously, with wavelengths ranging from 435 to 1600 nanometers.

With a huge, towering galaxy cluster in one field and no comparably massive objects in the other, the effects of both weak and strong gravitational lensing are readily apparent. The galaxy cluster--over 100 trillion times the mass of our sun--warps the fabric of space. This causes background light to bend around it, converging on our eyes another four billion light years away. From behind the cluster, the light from distant galaxies is stretched, magnified, distorted, and bent into arcs and multiple images: a classic example of strong gravitational lensing. But in a subtler fashion, the less optimally aligned galaxies are distorted as well; they are stretched into elliptical shapes along concentric circles surrounding the cluster.

A visual inspection yields more of these tangential alignments than radial ones in the cluster field, while the parallel field exhibits no such shape distortion. This effect, known as weak gravitational lensing, is a very powerful technique for obtaining galaxy cluster masses independent of any other conditions. In this serendipitous image, both types of lensing can be discerned by the naked eye. When the James Webb Space Telescope launches in 2018, gravitational lensing may well empower us to see all the way back to the very first stars and galaxies.

If you?re interested in teaching kids about how these large telescopes "see," be sure to see our article on this topic at the NASA Space Place: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/telescope-mirrors/en/

This article is provided by NASA Space Place. With articles, activities, crafts, games, and lesson plans, NASA Space Place encourages everyone to get excited about science and technology. Visit spaceplace.nasa.gov to explore space and Earth science!

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

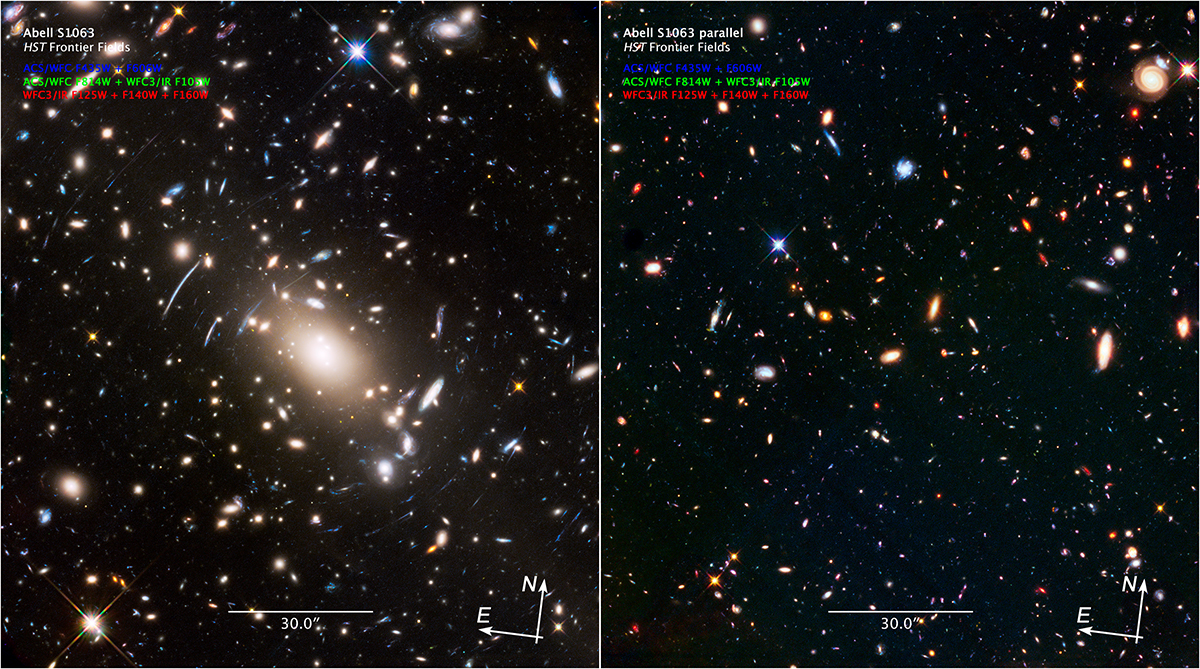

Galaxy cluster Abell S1063 (left) as imaged with the Hubble Space Telescope as part of the Frontier Fields program. The distorted images of the background galaxies are a consequence of the warped space dues to Einstein's general relativity; the parallel field (right) shows no such effects. Image credit: NASA, ESA and Jennifer Lotz (STScI)

Galaxy cluster Abell S1063 (left) as imaged with the Hubble Space Telescope as part of the Frontier Fields program. The distorted images of the background galaxies are a consequence of the warped space dues to Einstein's general relativity; the parallel field (right) shows no such effects. Image credit: NASA, ESA and Jennifer Lotz (STScI)

Oct. 1, 2016

Is Proxima Centauri's 'Earth-like' planet actually like Earth at all?

by Ethan Siegel

Just 25 years ago, scientists didn?t know if any stars-other than our own sun, of course-had planets orbiting around them. Yet they knew with certainty that gravity from massive planets caused the sun to move around our solar system?s center of mass. Therefore, they reasoned that other stars would have periodic changes to their motions if they, too, had planets.

This change in motion first led to the detection of planets around pulsars in 1991, thanks to the change in pulsar timing it caused. Then, finally, in 1995 the first exoplanet around a normal star, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered via the "stellar wobble" of its parent star. Since that time, over 3000 exoplanets have been confirmed, most of which were first discovered by NASA's Kepler mission using the transit method. These transits only work if a solar system is fortuitously aligned to our perspective; nevertheless, we now know that planets-even rocky planets at the right distance for liquid water on their surface-are quite common in the Milky Way.

On August 24, 2016, scientists announced that the stellar wobble of Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our sun, indicated the existence of an exoplanet. At just 4.24 light years away, this planet orbits its red dwarf star in just 11 days, with a lower limit to its mass of just 1.3 Earths. If verified, this would bring the number of Earth-like planets found in their star's habitable zones up to 22, with 'Proxima b' being the closest one. Just based on what we've seen so far, if this planet is real and has 130 percent the mass of Earth, we can already infer the following:

- It receives 70 percent of the sunlight incident on Earth, giving it the right temperature for liquid water on its surface, assuming an Earth-like atmosphere.

- It should have a radius approximately 10 percent larger than our own planet's, assuming it is made of similar elements.

- It is plausible that the planet would be tidally locked to its star, implying a permanent 'light side' and a permanent 'dark side'.

- And if so, then seasons on this world are determined by the orbit's ellipticity, not by axial tilt.

Yet the unknowns are tremendous. Proxima Centauri emits considerably less ultraviolet light than a star like the sun; can life begin without that? Solar flares and winds are much greater around this world; have they stripped away the atmosphere entirely? Is the far side permanently frozen, or do winds allow possible life there? Is the near side baked and barren, leaving only the 'ring' at the edge potentially habitable?

Proxima b is a vastly different world from Earth, and could range anywhere from actually inhabited to completely unsuitable for any form of life. As 30m-class telescopes and the next generation of space observatories come online, we just may find out!

Looking to teach kids about exoplanet discovery? NASA Space Place explains stellar wobble and how this phenomenon can help scientists find exoplanets: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/barycenter/en/

This article is provided by NASA Space Place. With articles, activities, crafts, games, and lesson plans, NASA Space Place encourages everyone to get excited about science and technology. Visit spaceplace.nasa.gov to explore space and Earth science!

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

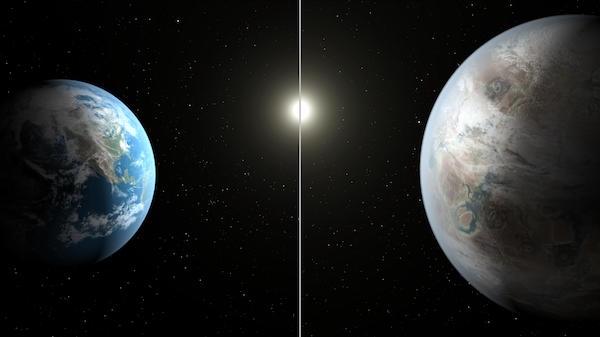

An artist?s conception of the exoplanet Kepler-452b (R), a possible candidate for Earth 2.0, as compared with Earth (L). Image credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle.

An artist?s conception of the exoplanet Kepler-452b (R), a possible candidate for Earth 2.0, as compared with Earth (L). Image credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle.

Nov. 1, 2016

Dimming stars, erupting plasma, and beautiful nebulae

by Marcus Woo

Boasting intricate patterns and translucent colors, planetary nebulae are among the most beautiful sights in the universe. How they got their shapes is complicated, but astronomers think they've solved part of the mystery-with giant blobs of plasma shooting through space at half a million miles per hour.

Planetary nebulae are shells of gas and dust blown off from a dying, giant star. Most nebulae aren't spherical, but can have multiple lobes extending from opposite sides-possibly generated by powerful jets erupting from the star.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers discovered blobs of plasma that could form some of these lobes. "We're quite excited about this," says Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Nobody has really been able to come up with a good argument for why we have multipolar nebulae."

Sahai and his team discovered blobs launching from a red giant star 1,200 light years away, called V Hydrae. The plasma is 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit and spans 40 astronomical units-roughly the distance between the sun and Pluto. The blobs don't erupt continuously, but once every 8.5 years.

The launching pad of these blobs, the researchers propose, is a smaller, unseen star orbiting V Hydrae. The highly elliptical orbit brings the companion star through the outer layers of the red giant at closest approach. The companion's gravity pulls plasma from the red giant. The material settles into a disk as it spirals into the companion star, whose magnetic field channels the plasma out from its poles, hurling it into space. This happens once per orbit-every 8.5 years-at closest approach.

When the red giant exhausts its fuel, it will shrink and get very hot, producing ultraviolet radiation that will excite the shell of gas blown off from it in the past. This shell, with cavities carved in it by the cannon-balls that continue to be launched every 8.5 years, will thus become visible as a beautiful bipolar or multipolar planetary nebula.

The astronomers also discovered that the companion's disk appears to wobble, flinging the cannonballs in one direction during one orbit, and a slightly different one in the next. As a result, every other orbit, the flying blobs block starlight from the red giant, which explains why V Hydrae dims every 17 years. For decades, amateur astronomers have been monitoring this variability, making V Hydrae one of the most well-studied stars.

Because the star fires plasma in the same few directions repeatedly, the blobs would create multiple lobes in the nebula-and a pretty sight for future astronomers.

If you'd like to teach kids about how our sun compares to other stars, please visit the NASA Space Place: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/sun-compare/en/

This article is provided by NASA Space Place. With articles, activities, crafts, games, and lesson plans, NASA Space Place encourages everyone to get excited about science and technology. Visit spaceplace.nasa.gov to explore space and Earth science!

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

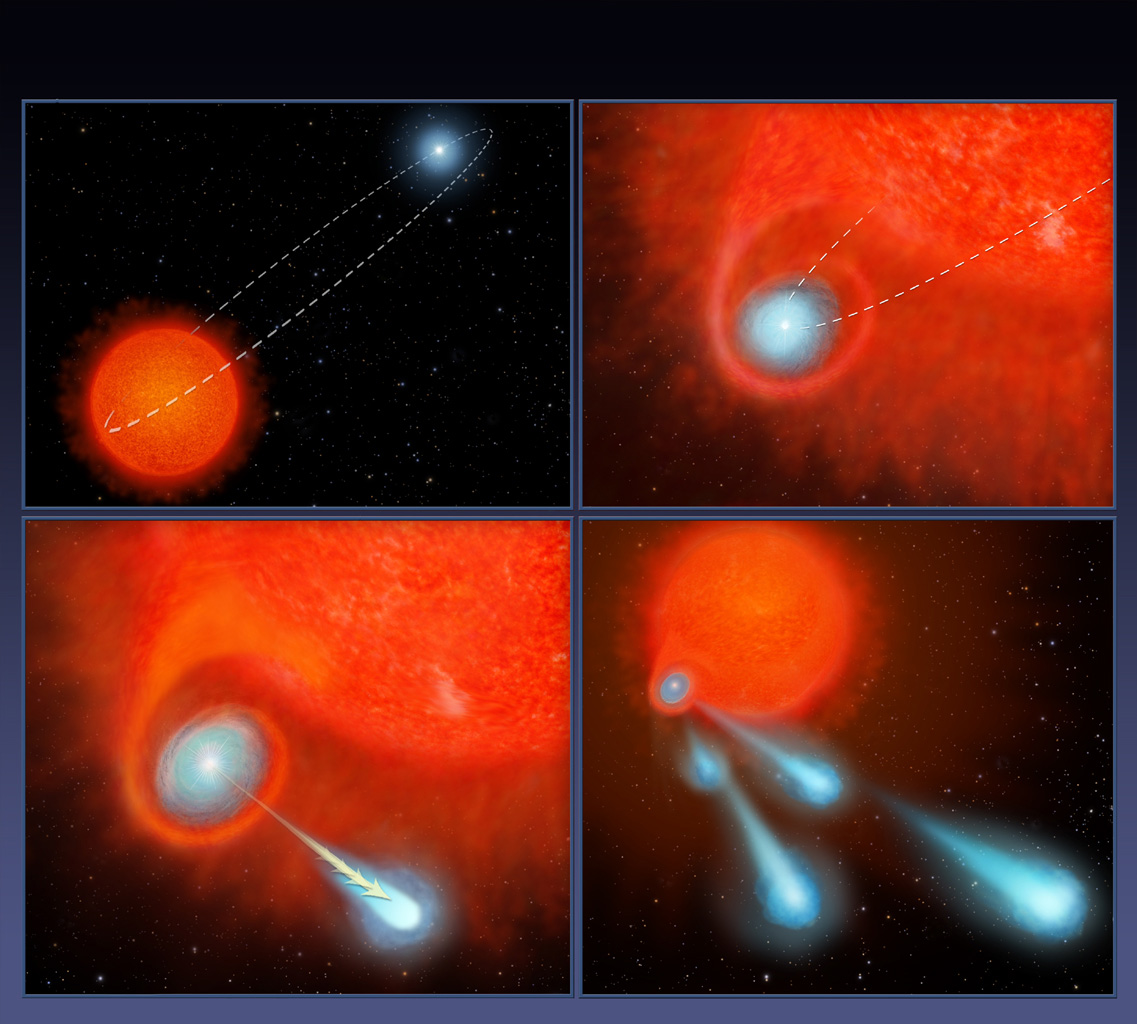

This four-panel graphic illustrates how the binary-star system V Hydrae is launching balls of plasma into space. Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI

This four-panel graphic illustrates how the binary-star system V Hydrae is launching balls of plasma into space. Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI