Next Launch

Total Students

2,609

Total Launches

683

Eggs Survived

418 61.2%

Rockets Survived

536 78.5%

July 1, 2014

The Invisible Shield of our Sun

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

Whether you look at the planets within our solar system, the stars within our galaxy or the galaxies spread throughout the universe, it's striking how empty outer space truly is. Even though the largest concentrations of mass are separated by huge distances, interstellar space isn't empty: it's filled with dilute amounts of gas, dust, radiation and ionized plasma. Although we've long been able to detect these components remotely, it's only since 2012 that a manmade spacecraft -- Voyager 1 -- successfully entered and gave our first direct measurements of the interstellar medium (ISM).

What we found was an amazing confirmation of the idea that our Sun creates a humongous "shield" around our solar system, the heliosphere, where the outward flux of the solar wind crashes against the ISM. Over 100 AU in radius, the heliosphere prevents the ionized plasma from the ISM from nearing the planets, asteroids and Kuiper belt objects contained within it. How? In addition to various wavelengths of light, the Sun is also a tremendous source of fast-moving, charged particles (mostly protons) that move between 300 and 800 km/s, or nearly 0.3% the speed of light. To achieve these speeds, these particles originate from the Sun's superheated corona, with temperatures in excess of 1,000,000 Kelvin!

When Voyager 1 finally left the heliosphere, it found a 40-fold increase in the density of ionized plasma particles. In addition, traveling beyond the heliopause showed a tremendous rise in the flux of intermediate-to-high energy cosmic ray protons, proving that our Sun shields our solar system quite effectively. Finally, it showed that the outer edges of the heliosheath consist of two zones, where the solar wind slows and then stagnates, and disappears altogether when you pass beyond the heliopause.

Unprotected passage through interstellar space would be life-threatening, as young stars, nebulae, and other intense energy sources pass perilously close to our solar system on ten-to-hundred-million-year timescales. Yet those objects pose no major danger to terrestrial life, as our Sun's invisible shield protects us from all but the rarer, highest energy cosmic particles. Even if we pass through a region like the Orion Nebula, our heliosphere keeps the vast majority of those dangerous ionized particles from impacting us, shielding even the solar system's outer worlds quite effectively. NASA spacecraft like the Voyagers, IBEX and SOHO continue to teach us more about our great cosmic shield and the ISM's irregularities. We're not helpless as we hurtle through it; the heliosphere gives us all the protection we need!

Want to learn more about Voyager 1's trip into interstellar space? Check this out: http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2013-278.

Kids can test their knowledge about the Sun at NASA's Space place: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/solar-tricktionary/.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Image credit: Hubble Heritage Team (AURA / STScI), C. R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt), and NASA, of the star LL Orionis and its heliosphere interacting with interstellar gas and plasma near the edge of the Orion Nebula (M42). Unlike our star, LL Orionis displays a bow shock, something our Sun will regain when the ISM next collides with us at a sufficiently large relative velocity.

Image credit: Hubble Heritage Team (AURA / STScI), C. R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt), and NASA, of the star LL Orionis and its heliosphere interacting with interstellar gas and plasma near the edge of the Orion Nebula (M42). Unlike our star, LL Orionis displays a bow shock, something our Sun will regain when the ISM next collides with us at a sufficiently large relative velocity.

Aug. 1, 2014

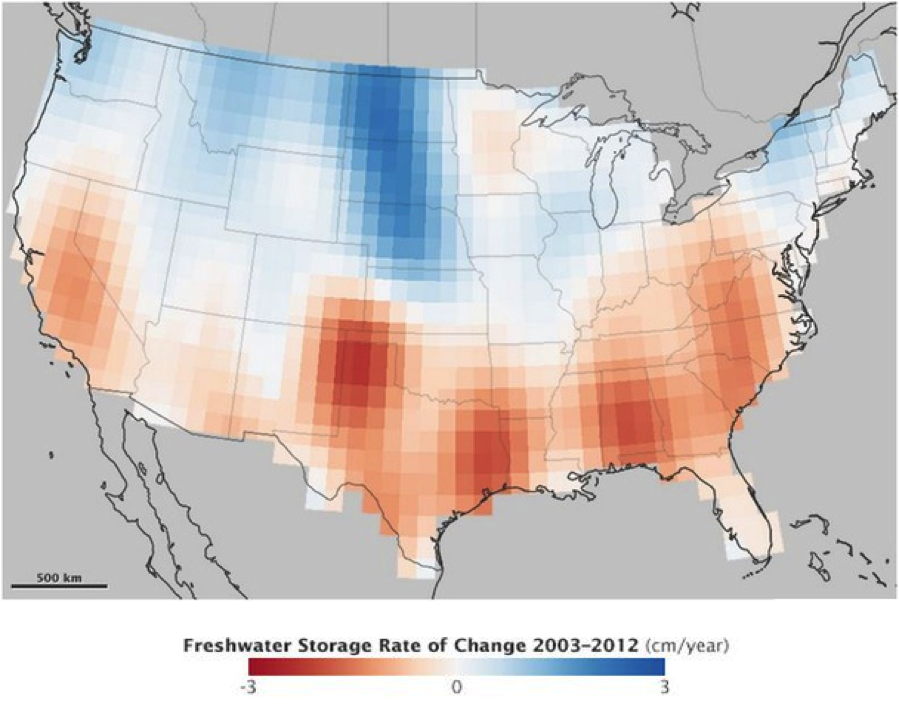

Droughts, Floods and the Earth's Gravity, by the GRACE of NASA

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

When you think about gravitation here on Earth, you very likely think about how constant it is, at 9.8 m/s2 (32 ft/s2). Only, that's not quite right. Depending on how thick the Earth's crust is, whether you're slightly closer to or farther from the Earth's center, or what the density of the material beneath you is, you'll experience slight variations in Earth's gravity as large as 0.2%, something you'd need to account for if you were a pendulum-clock-maker.

But surprisingly, the amount of water content stored on land in the Earth actually changes the gravity field of where you are by a significant, measurable amount. Over land, water is stored in lakes, rivers, aquifers, soil moisture, snow and glaciers. Even a change of just a few centimeters in the water table of an area can be clearly discerned by our best space-borne mission: NASA's twin Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites.

Since its 2002 launch, GRACE has seen the water-table-equivalent of the United States (and the rest of the world) change significantly over that time. Groundwater supplies are vital for agriculture and provide half of the world's drinking water. Yet GRACE has seen California's central valley and the southern high plains rapidly deplete their groundwater reserves, endangering a significant portion of the nation's food supply. Meanwhile, the upper Missouri River Basin-recently home to severe flooding-continues to see its water table rise.

NASA's GRACE satellites are the only pieces of equipment currently capable of making these global, precision measurements, providing our best knowledge for mitigating these terrestrial changes. Thanks to GRACE, we've been able to quantify the water loss of the Colorado River Basin (65 cubic kilometers), add months to the lead-time water managers have for flood prediction, and better predict the impacts of droughts worldwide. As NASA scientist Matthew Rodell says, "[W]ithout GRACE we would have no routine, global measurements of changes in groundwater availability. Other satellites can?t do it, and ground-based monitoring is inadequate." Even though the GRACE satellites are nearing the end of their lives, the GRACE Follow-On satellites will be launched in 2017, providing us with this valuable data far into the future. Although the climate is surely changing, it's water availability, not sea level rise, that's the largest near-term danger, and the most important aspect we can work to understand!

Learn more about NASA?s GRACE mission here: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/Grace/

Kids can learn al about launching objects into Earth?s orbit by shooting a (digital) cannonball on NASA?s Space Place website. Check it out at: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/how-orbits-work/

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using GRACE data provide courtesy of Jay Famigleitti, University of California Irvine and Matthew Rodell, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Caption by Holli Riebeek.

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using GRACE data provide courtesy of Jay Famigleitti, University of California Irvine and Matthew Rodell, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Caption by Holli Riebeek.

Sept. 1, 2014

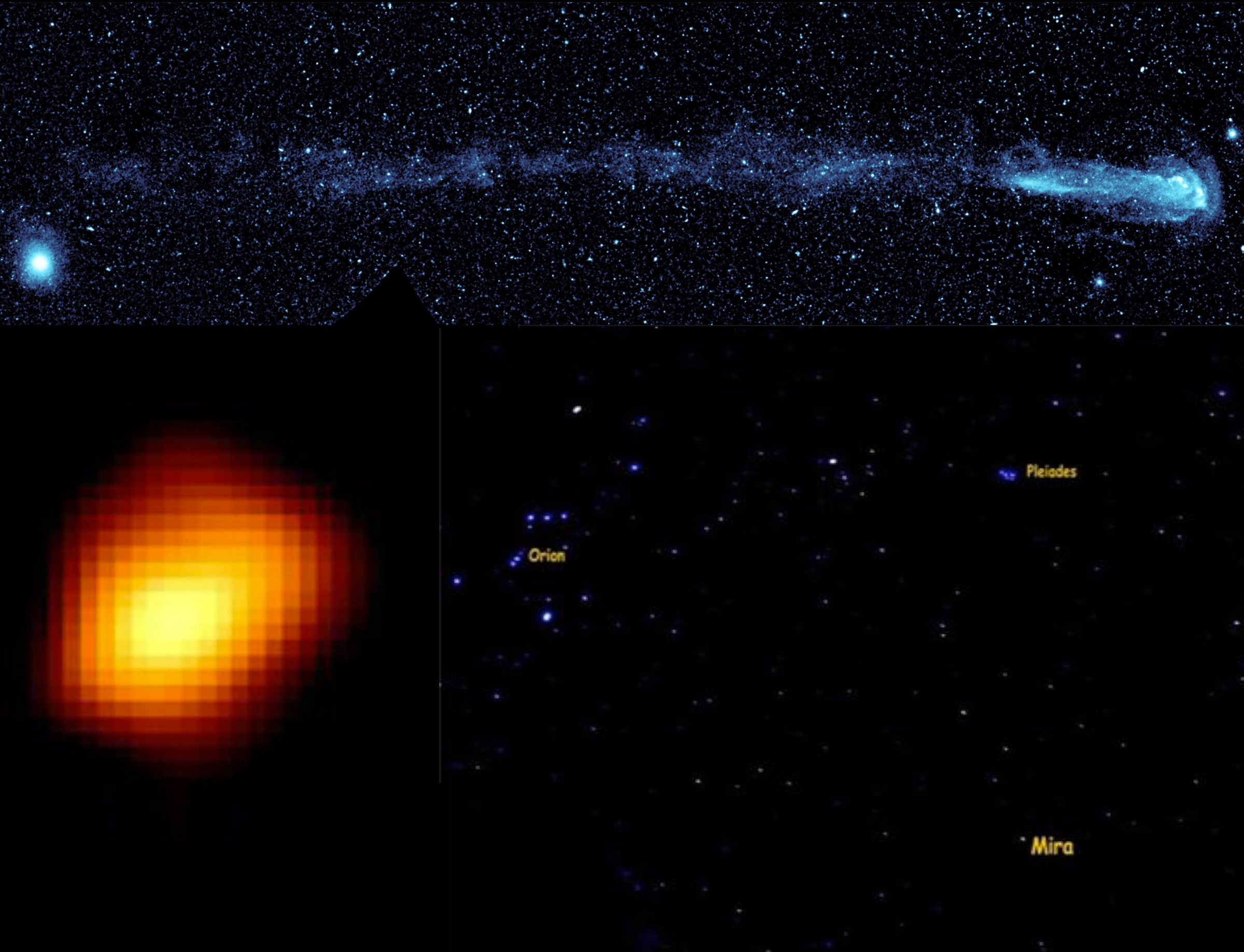

Twinkle, Twinkle, Variable Star

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

As bright and steady as they appear, the stars in our sky won't shine forever. The steady brilliance of these sources of light is powered by a tumultuous interior, where nuclear processes fuse light elements and isotopes into heavier ones. Because the heavier nuclei up to iron (Fe), have a greater binding energies-per-nucleon, each reaction results in a slight reduction of the star's mass, converting it into energy via Einstein's famous equation relating changes in mass and energy output, E = mc2. Over timescales of tens of thousands of years, that energy migrates to the star's photosphere, where it's emitted out into the universe as starlight.

There's only a finite amount of fuel in there, and when stars run out, the interior contracts and heats up, often enabling heavier elements to burn at even higher temperatures, and causing sun-like stars to grow into red giants. Even though the cores of both hydrogen-burning and helium-burning stars have consistent, steady energy outputs, our sun's overall brightness varies by just ~0.1%, while red giants can have their brightness?s vary by factors of thousands or more over the course of a single year! In fact, the first periodic or pulsating variable star ever discovered-Mira (omicron Ceti)-behaves exactly in this way.

There are many types of variable stars, including Cepheids, RR Lyrae, cataclysmic variables and more, but it's the Mira-type variables that give us a glimpse into our Sun's likely future. In general, the cores of stars burn through their fuel in a very consistent fashion, but in the case of pulsating variable stars the outer layers of stellar atmospheres vary. Initially heating up and expanding, they overshoot equilibrium, reach a maximum size, cool, then often forming neutral molecules that behave as light-blocking dust, with the dust then falling back to the star, ionizing and starting the whole process over again. This temporarily neutral dust absorbs the visible light from the star and re-emits it, but as infrared radiation, which is invisible to our eyes. In the case of Mira (and many red giants), it's Titanium Monoxide (TiO) that causes it to dim so severely, from a maximum magnitude of +2 or +3 (clearly visible to the naked eye) to a minimum of +9 or +10, requiring a telescope (and an experienced observer) to find!

Visible in the constellation of Cetus during the fall-and-winter from the Northern Hemisphere, Mira is presently at magnitude +7 and headed towards its minimum, but will reach its maximum brightness again in May of next year and every 332 days thereafter. Shockingly, Mira contains a huge, 13 light-year-long tail -- visible only in the UV -- that it leaves as it rockets through the interstellar medium at 130 km/sec! Look for it in your skies all winter long, and contribute your results to the AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers) International Database to help study its long-term behavior!

Check out some cool images and simulated animations of Mira here: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/galex/20070815/v.html

Kids can learn all about Mira at NASA?s Space Place: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/mira/en/

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) spacecraft, of Mira and its tail in UV light (top); Margarita Karovska (Harvard-Smithsonian CfA) / NASA's Hubble Space Telescope image of Mira, with the distortions revealing the presence of a binary companion (lower left); public domain image of Orion, the Pleiades and Mira (near maximum brightness) by Brocken Inaglory of Wikimedia Commons under CC-BY-SA-3.0 (lower right).

NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) spacecraft, of Mira and its tail in UV light (top); Margarita Karovska (Harvard-Smithsonian CfA) / NASA's Hubble Space Telescope image of Mira, with the distortions revealing the presence of a binary companion (lower left); public domain image of Orion, the Pleiades and Mira (near maximum brightness) by Brocken Inaglory of Wikimedia Commons under CC-BY-SA-3.0 (lower right).

Sept. 1, 2014

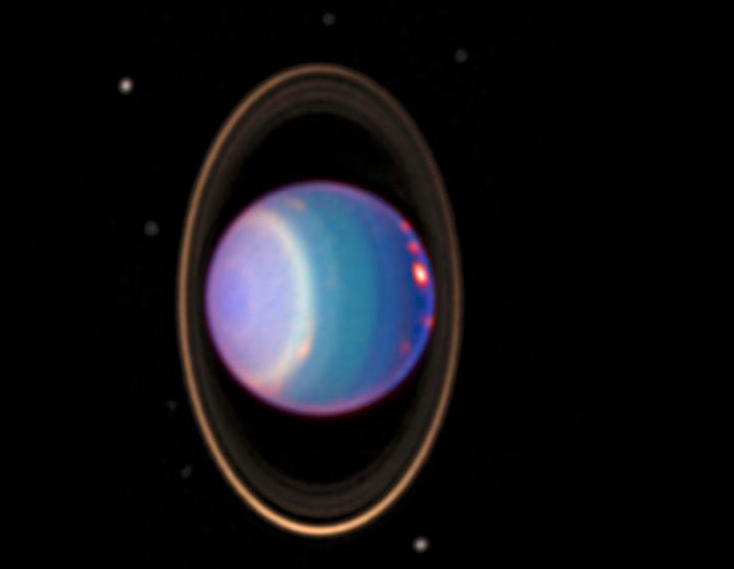

Why Did It Take So Long To Discover Uranus?

by Nasa's Space Place

Read all about the discovery of Uranus in the Space Place's latest column: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/uranus.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Hubble telescope image of Uranus. Credit:NASA/JPL/STScI.

Hubble telescope image of Uranus. Credit:NASA/JPL/STScI.