Next Launch

Total Students

2,609

Total Launches

683

Eggs Survived

418 61.2%

Rockets Survived

536 78.5%

Aug. 1, 2013

Size Does Matter, But So Does Dark Energy

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

Here in our own galactic backyard, the Milky Way contains some 200-400 billion stars, and that's not even the biggest galaxy in our own local group. Andromeda (M31) is even bigger and more massive than we are, made up of around a trillion stars! When you throw in the Triangulum Galaxy (M33), the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, and the dozens of dwarf galaxies and hundreds of globular clusters gravitationally bound to us and our nearest neighbors, our local group sure does seem impressive.

Yet that's just chicken feed compared to the largest structures in the universe. Giant clusters and superclusters of galaxies, containing thousands of times the mass of our entire local group, can be found omnidirectionally with telescope surveys. Perhaps the two most famous examples are the nearby Virgo Cluster and the somewhat more distant Coma Supercluster, the latter containing more than 3,000 galaxies. There are millions of giant clusters like this in our observable universe, and the gravitational forces at play are absolutely tremendous: there are literally quadrillions of times the mass of our Sun in these systems.

The largest superclusters line up along filaments, forming a great cosmic web of structure with huge intergalactic voids in between the galaxy-rich regions. These galaxy filaments span anywhere from hundreds of millions of light-years all the way up to more than a billion light years in length. The CfA2 Great Wall, the Sloan Great Wall, and most recently, the Huge-LQG (Large Quasar Group) are the largest known ones, with the Huge-LQG -- a group of at least 73 quasars - apparently stretching nearly 4 billion light years in its longest direction: more than 5% of the observable universe! With more mass than a million Milky Way galaxies in there, this structure is a puzzle for cosmology.

You see, with the normal matter, dark matter, and dark energy in our universe, there's an upper limit to the size of gravitationally bound filaments that should form. The Huge-LQG, if real, is more than double the size of that largest predicted structure, and this could cast doubts on the core principle of cosmology: that on the largest scales, the universe is roughly uniform everywhere. But this might not pose a problem at all, thanks to an unlikely culprit: dark energy. Just as the local group is part of the Virgo Supercluster but recedes from it, and the Leo Cluster -- a large member of the Coma Supercluster -- is accelerating away from Coma, it's conceivable that the Huge-LQG isn't a single, bound structure at all, but will eventually be driven apart by dark energy. Either way, we're just a tiny drop in the vast cosmic ocean, on the outskirts of its rich, yet barely fathomable depths.

Learn about the many ways in which NASA strives to uncover the mysteries of the universe: http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/. Kids can make their own clusters of galaxies by checking out The Space Place's fun galactic mobile activity: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/galactic-mobile/

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The Coma Cluster, the largest member of the Coma Supercluster. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Goddard Space Flight Center / Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

The Coma Cluster, the largest member of the Coma Supercluster. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Goddard Space Flight Center / Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Sept. 1, 2013

How to Hunt for Your Very Own Supernova!

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

In our day-to-day lives, stars seem like the most fixed and unchanging of all the night sky objects. Shining relentlessly and constantly for billions of years, it's only the long-term motion of these individual nuclear furnaces and our own motion through the cosmos that results in the most minute, barely-perceptible changes.

Unless, that is, you're talking about a star reaching the end of its life. A star like our Sun will burn through all the hydrogen in its core after approximately 10 billion years, after which the core contracts and heats up, and the heavier element helium begins to fuse. About a quarter of all stars are massive enough that they'll reach this giant stage, but the most massive ones -- only about 0.1% of all stars -- will continue to fuse leaner elements past carbon, oxygen, neon, magnesium, silicon, sulphur and all the way up to iron, cobalt, and, nickel in their core. For the rare ultra-massive stars that make it this far, their cores become so massive that they're unstable against gravitational collapse. When they run out of fuel, the core implodes.

The inrushing matter approaches the center of the star, then rebounds and bounces outwards, creating a shockwave that eventually causes what we see as a core-collapse supernova, the most common type of supernova in the Universe! These occur only a few times a century in most galaxies, but because it's the most massive, hottest, shortest-lived stars that create these core-collapse supernovae, we can increase our odds of finding one by watching the most actively star-forming galaxies very closely. Want to maximize your chances of finding one for yourself? Here's how.

Pick a galaxy in the process of a major merger, and get to know it. Learn where the foreground stars are, where the apparent bright spots are, what its distinctive features are. If a supernova occurs, it will appear first as a barely perceptible bright spot that wasn't there before, and it will quickly brighten over a few nights. If you find what appears to be a "new star" in one of these galaxies and it checks out, report it immediately; you just might have discovered a new supernova!

This is one of the few cutting-edge astronomical discoveries well-suited to amateurs; Australian Robert Evans holds the all-time record with 42 (and counting) original supernova discoveries. If you ever find one for yourself, you'll have seen an exploding star whose light traveled millions of light-years across the Universe right to you, and you'll be the very first person who's ever seen it!

Read more about the evolution and ultimate fate of the stars in our universe: http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/focus-areas/how-do-stars-form-and-evolve/.

While you are out looking for supernovas, kids can have a blast finding constellations using the Space Place star finder: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/starfinder/.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

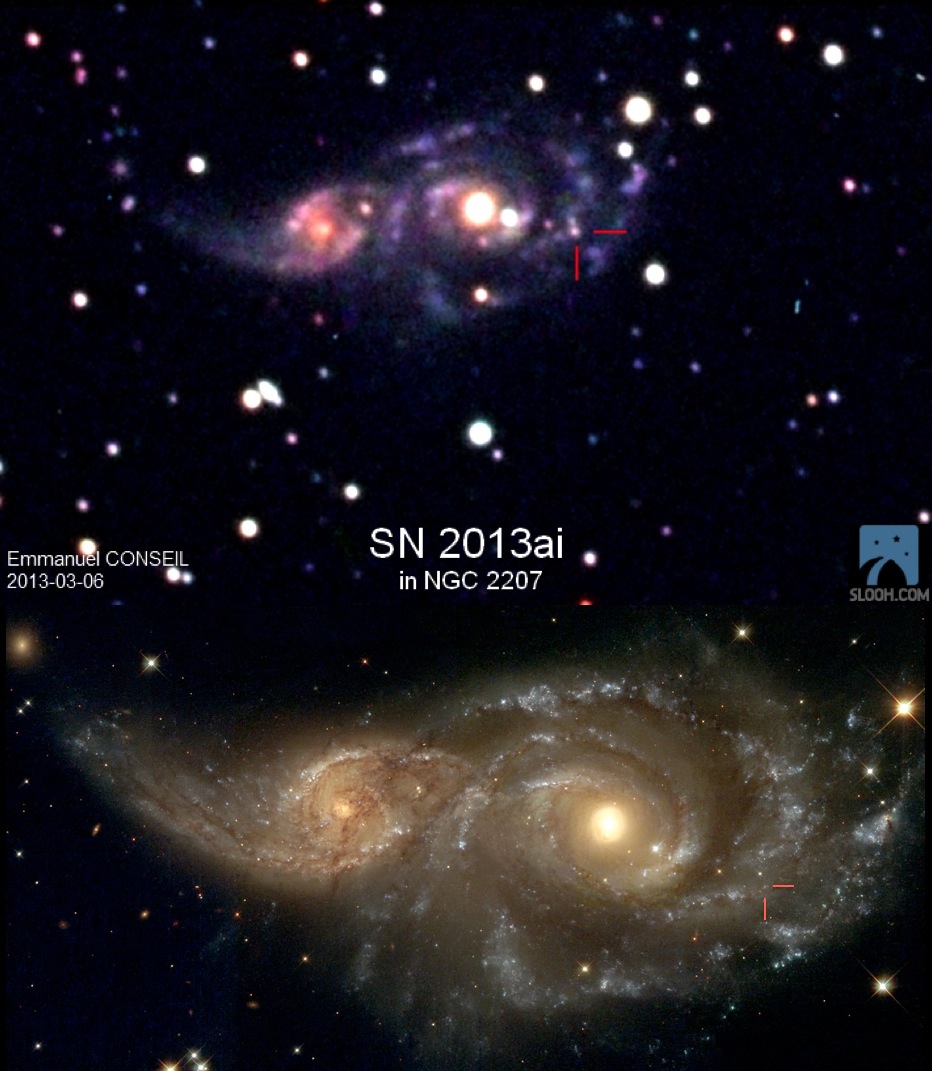

SN 2013ai, via its discoverer, Emmanuel Conseil, taken with the Slooh.com robotic telescope just a few days after its emergence in NGC 2207 (top); NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI) of the same interacting galaxies prior to the supernova (bottom).

SN 2013ai, via its discoverer, Emmanuel Conseil, taken with the Slooh.com robotic telescope just a few days after its emergence in NGC 2207 (top); NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI) of the same interacting galaxies prior to the supernova (bottom).

Oct. 1, 2013

Government Shutdown - Oct 2013

by Laura K. Lincoln

Dear Space Place partners,

Our apologies for the inconvenience, but unless the United States federal government shutdown is resolved by October 11, 2013, we will be unable to deliver the October article.

NASA's Space Place is a NASA educational website about space and Earth sciences and technologies for upper-elementary-aged-children.

Best wishes,

Laura K. Lincoln, on behalf of the NASA's Space Place Team

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

NASA's Space Place is a NASA educational website about space and Earth sciences and technologies for upper-elementary-aged-children.

NASA's Space Place is a NASA educational website about space and Earth sciences and technologies for upper-elementary-aged-children.

Nov. 1, 2013

The Most Volcanically Active Place is Out-of-this-World!

by Dr. Ethan Siegel

Volcanoes are some of the most powerful and destructive natural phenomena, yet they're a vital part of shaping the planetary landscape of worlds small and large. Here on Earth, the largest of the rocky bodies in our Solar System, there's a tremendous source of heat coming from our planet's interior, from a mix of gravitational contraction and heavy, radioactive elements decaying. Our planet consistently outputs a tremendous amount of energy from this process, nearly three times the global power production from all sources of fuel. Because the surface-area-to-mass ratio of our planet (like all large rocky worlds) is small, that energy has a hard time escaping, building-up and releasing sporadically in catastrophic events: volcanoes and earthquakes!

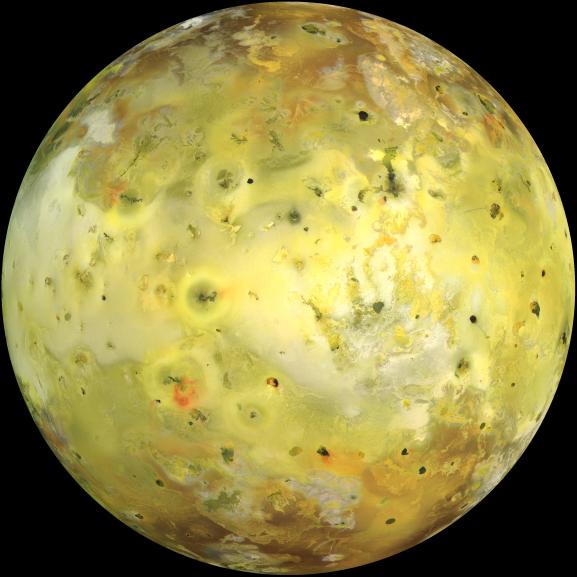

Yet volcanoes occur on worlds that you might never expect, like the tiny moon Io, orbiting Jupiter. With just 1.5% the mass of Earth despite being more than one quarter of the Earth's diameter, Io seems like an unlikely candidate for volcanoes, as 4.5 billion years is more than enough time for it to have cooled and become stable. Yet Io is anything but stable, as an abundance of volcanic eruptions were predicted before we ever got a chance to view it up close. When the Voyager 1 spacecraft visited, it found no impact craters on Io, but instead hundreds of volcanic calderas, including actual eruptions with plumes 300 kilometers high! Subsequently, Voyager 2, Galileo, and a myriad of telescope observations found that these eruptions change rapidly on Io's surface.

Where does the energy for all this come from? From the combined tidal forces exerted by Jupiter and the outer Jovian moons. On Earth, the gravity from the Sun and Moon causes the ocean tides to raise-and-lower by one-to-two meters, on average, far too small to cause any heating. Io has no oceans, yet the tidal forces acting on it cause the world itself to stretch and bend by an astonishing 100 meters at a time! This causes not only cracking and fissures, but also heats up the interior of the planet, the same way that rapidly bending a piece of metal back-and-forth causes it to heat up internally. When a path to the surface opens up, that internal heat escapes through quiescent lava flows and catastrophic volcanic eruptions! The hottest spots on Io's surface reach 1,200 degrees C (2,000 degrees F); compared to the average surface temperature of 110 Kelvin (-163 degrees C / -261 degrees F), Io is home to the most extreme temperature differences from location-to-location outside of the Sun.

Just by orbiting where it does, Io gets distorted, heats up, and erupts, making it the most volcanically active world in the entire Solar System! Other moons around gas giants have spectacular eruptions, too (like Enceladus around Saturn), but no world has its surface shaped by volcanic activity quite like Jupiter's innermost moon, Io!

Learn more about Galileo?s mission to Jupiter: http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/galileo/.

Kids can explore the many volcanoes of our solar system using the Space Place?s Space Volcano Explorer: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/volcanoes.

This article was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Io. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech, via the Galileo spacecraft.

Io. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech, via the Galileo spacecraft.